Chickasaw veteran completes personal mission in Washington

CONTRIBUTED BY Tony Choate, Media Relations.

This article appeared in the December 2014 edition of the Chickasaw Times

Leonard Sealey had one primary mission in mind during his recent trip to Washington, D.C. He was going to find one particular name etched into the black marble of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

“It happened really fast,” Mr. Sealey said as he relayed vivid memories of the events in Vietnam almost 50 years ago that led to his quest.

“We were almost on the ground. We knew it was a hot LZ (landing zone),” he said.

“We never did land,” he said, explaining standard operating procedure of his helicopter crew in Vietnam. “We would get about three or four feet from the ground then those infantry guys would jump off.”

It was relatively rare for his helicopter to be hit by machine gun fire as they delivered troops to various destinations in that Southeast Asian country. They were very surprised when they realized they were being fired on this day as they were the third helicopter to drop troops at this particular destination.

The rounds began to tear into the ship as it reached the drop point near sunset on March 30, 1965.

“Two other bunches of the infantry guys had already jumped off when we came in and I saw this machine gun fire, tracers. About every fifth round you can see the orange tracers fly.”

As he prepared to return fire with his machine gun, he bent over for some reason he still can’t recall. Just at that moment the Viet Cong machine gun sent a spray of bullets ripping through the side of their helicopter.

“When I sat back up - I didn’t know I had bullet holes right beside me – the copilot told me to get up there and get Captain Blanton off the controls.”

Capt. Blanton, the pilot of the Huey, had been killed instantly by a bullet through his throat. His left leg stiffened on the foot pedal that controlled the tail rotor which destabilized the helicopter, causing the helicopter to spin out of control.

As Mr. Sealey grabbed the pilot and pulled him off the foot pedals, several of the infantrymen on ship jumped to the ground.

As Mr. Sealey desperately pulled Capt. Blanton off the pedal, the copilot pulled up on the stick to keep it from crashing into the ground. As the ship rose, he finally regained control of the just before it crashed into a stand of tall trees.

After they had cleared the trees, there was precious little the copilot could do to maintain control of the ship, which had taken a direct hit to its engine and transmission. Fuel and oil poured from tanks ruptured by the machine gun fire.

“We had to land it,” Mr. Sealey recalled with a sense of urgency in his voice. “I remember I was still holding Captain Blanton when we came in. The rotor blades were just almost ready to quit. When we came down we hit the ground hard. We bounced like that, and that and that,” he said, slapping his hands together hard to demonstrate the impact. “That helicopter just started falling apart. The doors were coming off of it, we skidded and hit the ground and tipped up and over.”

He was still holding Capt. Blanton when several GIs came running to their rescue from a Chinook helicopter that had responded their distress calls. A stunned Mr. Sealey finally handed the pilot off to the rescuers before the Chinook took the rest of the crew to safety. Miraculously, none of the other crew members had been injured.

“I couldn’t believe how that happened, that he got shot and I didn’t,” he said. “We were only about two feet apart. I was sitting right there beside him, just like you and I are sitting here next to each other,” he said, motioning the distance with his hand.

He never saw Capt. Blanton, or the copilot who helped save his life again.

“That was the first death of a GI that I knew. There were a lot of others that happened, but it was the first one I saw,” he said, adding that he was still nervous and shaking when he got back to his unit.

“Over there, we weren’t just officers and enlisted men,” he said. “We were a team. We stayed together day and night. I slept in that helicopter. We parked it at night I’d get my sleeping bag and I slept in it. That was MY house.”

While he had the option to take some time off to recover from the emotional shock, he chose to go back to the only life he had known for the previous eight months.

“We got another helicopter. I went right back to work. I didn’t want to sit around,” he said. “I was scared. I won’t say I wasn’t, but I’d rather – I’d done that four or five months, so I was used to it.”

They worked seven days a week transporting troops to the landing zones. He rarely had the chance to see the men again after they delivered them to their destinations.

A few months later his tour was over and he returned to the U.S. Since coming back, he has never seen another man from his unit in Vietnam.

Maybe that is why it was so important to find that one familiar name on the wall.

While he was unsure just what would happen when he found the name, he didn’t break down into tears as so many others have. Maybe it was because he was able to see a Huey Helicopter similar to the one he called home when he visited the Udvar-Hazy Center a few days earlier.

“It really hit me pretty hard,” he said. “I stood there and looked at that thing. It brought back a lot of memories.”

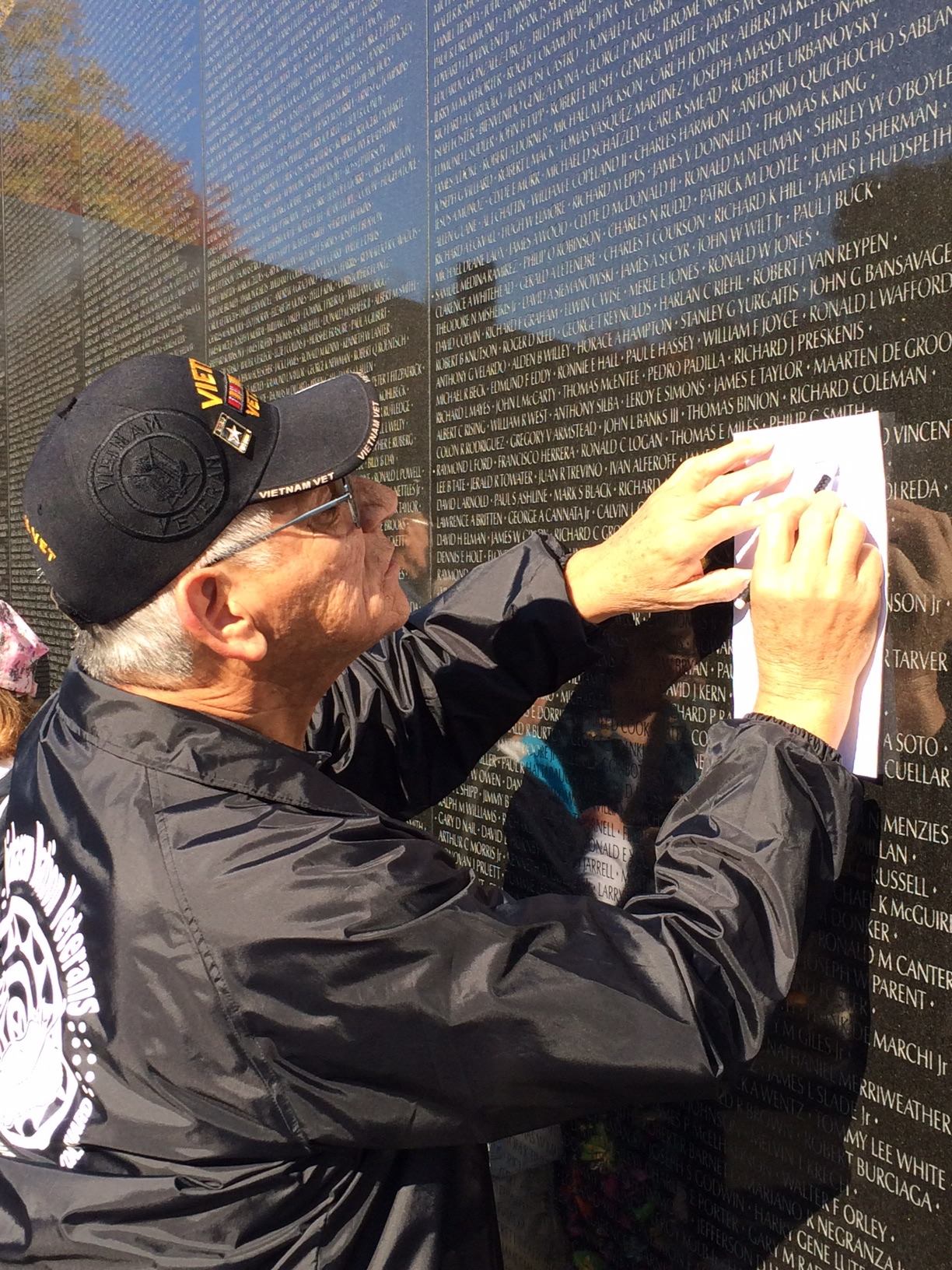

When he found the name of Capt. Blanton on the wall, he was able to able to take one of those memories home in the tangible form of an impression of the name made with pencil and paper.

His mission was complete.

Mr. Sealey is one of 16 Chickasaw veterans who recently took a trip to Washington sponsored by the Chickasaw Nation.

Many of the other Vietnam veterans on the trip made a point to visit “the wall” to find names of men with whom they had served. There were more than a few tears from members of the group as they visited the memorial.

The group, which includes veterans from Oklahoma, Texas, Rhode Island, Montana, Louisiana. Arkansas and California, visited Washington November 7 through November 12.